Beer Bowl: More colleges in search of revenue turn to alcohol sales at sports games

It seems more and more colleges across the country have finally put one-and-one together: sports and alcohol.

In spite of safety and image concerns, colleges in dire need of additional revenues to pay for their ever-expanding budgets are turning to beer to shore up their bottom lines.

Currently, the NCAA only explicitly bans alcohol sales at the championship events that it oversees. For regular season games the decision to sell alcohol is left up to individual schools and divisions. Over a fifth of Division I football schools do in fact allow alcohol sales at their games, but some—perhaps most notably the California State University system and the Southeastern Conference (SEC)—strictly prohibit it.

Some of the schools offering beer at their concession stands include University of Houston, Louisville, University of Memphis, Tulane, and University of Minnesota, according to USA Today.

There is some get-around, though, for those attending games at ‘dry’ colleges: alcohol is often available to those seated in luxury seating areas even if it’s banned elsewhere in the stadium.

The major rationale behind the push to sell alcohol to anyone 21 and up seated anywhere in the stadium is for the increased revenue. Three years ago, West Virginia University brought beer to its football game concession stands and reaped in an additional $500,000 in concessions in the first year. According to The Richest, schools can make even more money by selling contracts to beer providers to be exclusive providers at their games or stadiums.

At the school your correspondent attends, alcohol is not sold at any sports games, but if it did:

For the 2013-14 season, this school’s Division I football team played five out of ten games at home with an average attendance per game of 7,002—about 27% capacity of the stadium. (Note: football is not very popular at this school and this season the team’s record was 3-7.) Using the 2013 NFL season’s average price of $7.05 for a small draft beer, the total revenue from beer sales assuming half the attendees bought just one would have been $24,682 per game or $123,410 for all five home games. Assuming that alcohol sales would double average attendance and that these additional 7,002 people all buy one beer (after all, they are attending just because alcohol is now sold), then the revenue per game would be $74,046 or $370,230 for all five home games. Double these figures if two beers (the usual maximum at college sports games) are purchased. Plus, the increased attendance would translate into more ticket sales and higher food concessions for the beer to go down with.

While it is undoubtedly in the interest of the university, law enforcement, medical professionals, and local residents to reduce the amount of drinking at colleges, one of the major benefits of selling alcohol at college games might just be increased safety.

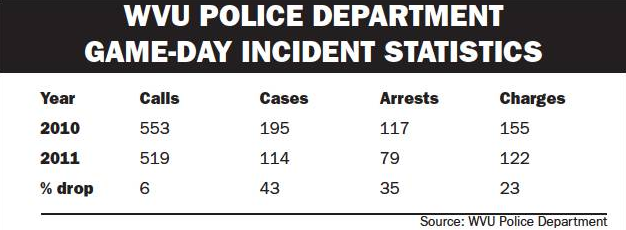

The West Virginia Police Department records show that in the first year of alcohol sales cases dropped by 43% and arrests by 35%. This result, however, contradicts a study that found a significant decrease in arrests and assaults after the University of Colorado-Boulder banned alcohol sales in 1996.

The increased-safety argument centers on the supposed reduction in high-risk drinking activities—namely, unsupervised binge drinking before games.

As many on and off the campus know, students older and younger than 21 often participate in “pre-gaming” or tailgating to get ‘buzzed’ or drunk before large sports events specifically because they cannot at the event. Often, hard liquor is consumed in order to get drunk quickly and prolong the state of intoxication. Alternatively or additionally, alcohol—again, usually hard liquor—is snuck into games.

Mark Thornton at the Ludwig Von Mises Institutes argues in a published article that in-stadium alcohol sales would partially stem these dangerous activities. He also expounds on the advantages of selling beer over smuggling in hard liquors:

Fans that drink alcohol while tailgating are almost exclusively beer drinkers, both before and after the game. But, when it comes to getting past stadium security their choice is “spirits” — usually the strongest, highest proof varieties of rum and whiskey. To help, a variety of local stores carry products that cater to the “need” to conceal “spirits.

For example, if you put 16 ounces of Bacardi 151 Rum (75 percent alcohol) into a pint flask you would have the alcohol equivalent of 20, 12-ounce bottles of Budweiser. This stuff is so strong that it can catch on fire! It is normally used in specialty drinks and cooking, but it’s also a top seller on college football weekends.

And it is not just the total amount of alcohol, but how fast it is consumed. Beer-drinking football fans typically have what is called a “pace.” The pace is how many beers they drink in an hour without getting clumsy, obnoxious, and stupid. It might be one, two, or three beers in an hour depending on your size, sex, age, and tolerance. Drinking more than your normal pace can get you in trouble.

The problem with our beer-drinking football fan is that one mistaken; unmeasured pour of 151 can mean big trouble. If he pours approximately ¾ of an ounce into a 12-ounce cola drink, with ice, works out to the alcohol equivalent of one light beer.

However, if a little more than 4 ounces is accidentally, or intentionally, poured into the cup, then the cola is equivalent to a 6-pack of beer. This one bad pour could easily lead to a second unfortunate pour, and, … you probably get the picture.

Since curbing alcohol consumption among college students is a lofty, unattainable goal, it seems wise to tap into the college student thirst to shore up athletic spending.

Comments

Because drunk students get better grades? How stupid!