Harvard Museum of Science and Culture Hosts Bob Brier’s “Egyptomania” Talk

The 1922 of King Tutankamon’s tomb spatked latest wave of “Egyptomania” to wash over the world, according to Bob Brier, a Long Island University senior research fellow and Egyptologist with a particular expertise in mummies.

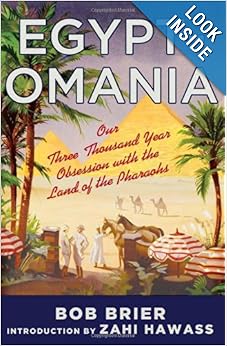

Brier recently reviewed the history of Egyptomania, which is the topic of his latest book, in a talk recently sponsored by sponsored by the Semitic Museum (one of the Harvard Museums of Science and Culture).

The phenomenon started in force more than 200 years ago, Brier says, with Napoleon Bonaparte’s 1798 invasion of Egypt, where he defeated a Mamluk army in a battle fought near Cairo, within sight of the pyramids. French rule of the country wouldn’t last long, collapsing after British Admiral Horatio Nelson destroyed the French fleet days later in the Battle of the Nile.

But Napoleon did not go away empty-handed. His gains included the records of more than 100 artists, engineers, and scientists who, as the fighting raged, collected, drew, and documented the natural and manmade wonders of Egypt. The publication of their work in France fed a curiosity that hasn’t faded. According to Brier, it flows largely from three spheres of interest: mummies, the mystery of hieroglyphics, and the allure of a lost civilization, epitomized by Carter’s discovery of Tut’s tomb.

…Since the Battle of the Pyramids, several events have fueled interest around ancient Egypt, said Brier, citing as especially important the delivery of Egyptian obelisks to France, Britain, and the United States.

The first, which left Egypt for France in 1832, required more than three years for transport and placement in the Place de la Concorde in Paris. The British obelisk, which left Egypt in 1877, towed behind a steamship in a specially built vessel, was lost at sea in a storm, salvaged, and had to be bought back by the government. The last obelisk was erected in Central Park in 1881. It took 112 days to slowly move the 244-ton, 71-foot, hieroglyphic-inscribed obelisk to the park from the banks of the Hudson River.

Each of these events — capped by the discovery of Tut’s tomb in 1922 — stoked public enthusiasm, Brier said. Egyptian-themed products — jewelry, songs, and tobacco — followed. Egypt sells, Brier said, and people hustled to cash in.

Much of the talk dealt with history, but Brier was quick to point out that the artifacts and mystery of ancient Egypt haven’t lost any of their power.

“Egyptomania is still alive and well today,” he said.